You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

John Perry is a policy advisor at the Chartered Institute of Housing

Government policy needs to return to building homes let at modest rents

As the latest UK Housing Review is published, co-author John Perry describes how government priorities have shifted from direct investment in affordable housing to personal subsidy through housing benefit

If asked about how the government spends money on housing, most people would probably say they build council houses – but of course they’d be wrong.

However, if the same question had been asked in the 1970s the answer would have been a lot closer to the truth.

Over the course of nearly four decades, there have been drastic shifts in how the government spends money on housing.

The latest UK Housing Review summarises them.

It’s no surprise that government direct investment in housing has gone down.

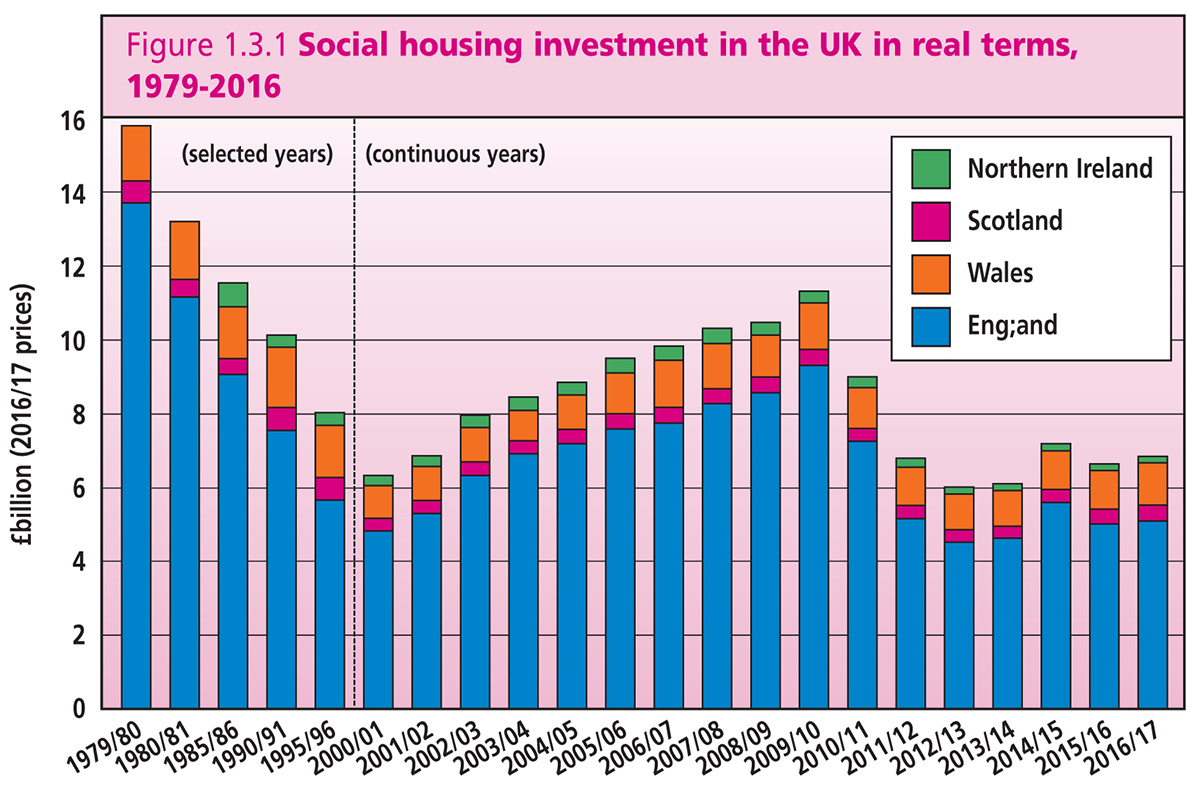

Our first chart from the UK Housing Review (below) shows by how much.

In today’s prices, back in 1979 the government was investing almost £16bn in housing across the UK.

It fell away sharply in the 1980s and 1990s, but 30 years later it had climbed back to about £11bn, only to fall again to less than £7bn today.

In England, a lot of this investment has come from local authorities – 80% of it back in 1979/80, when councils were still getting significant government subsidy, rising to a staggering 94% today, when the only local authority receiving subsidy is the Greater London Authority (GLA), because it acts as the grant provider to London social landlords.

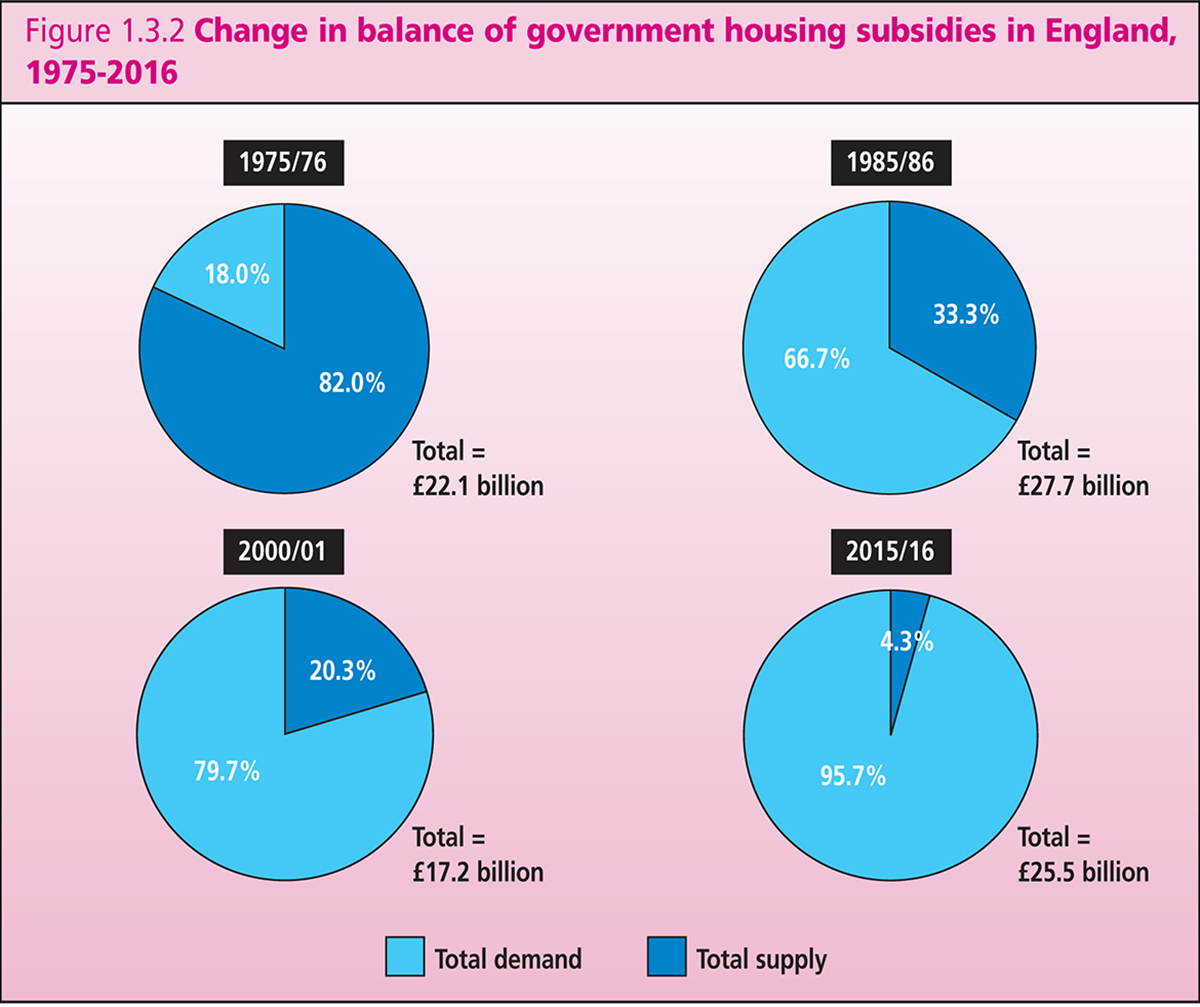

Another way of looking at the shift in government priorities is to compare its investment in improving housing supply with its subsidies for sustaining housing demand.

In the first category are its grants for building, and in the second the big elements are housing benefit and some other personal subsidies like support for mortgage interest payments.

Our second chart (below) shows how this balance has changed.

Back in the mid-1970s, more than four-fifths of government subsidy was being put into investment in bricks and mortar, mainly into building new homes.

“Today, personal subsidies almost totally dominate the use of direct government spending on housing.”

Within a decade, personal subsidies had grown to take up two-thirds of spending, with the trend was to get worse.

Today, personal subsidies almost totally dominate the use of direct government spending on housing, as the housing benefit bill has grown from a tiny amount 40 years ago to more than £24bn now.

From the 1980s onwards, the government allowed housing benefit ‘to take the strain’ of paying for housing investment.

Warnings of problems ahead went unheeded by governments of both main parties, until George Osborne when chancellor started to cut back housing benefit expenditure, but without compensating for the cuts by investing in new homes at rents that tenants could pay without needing benefits.

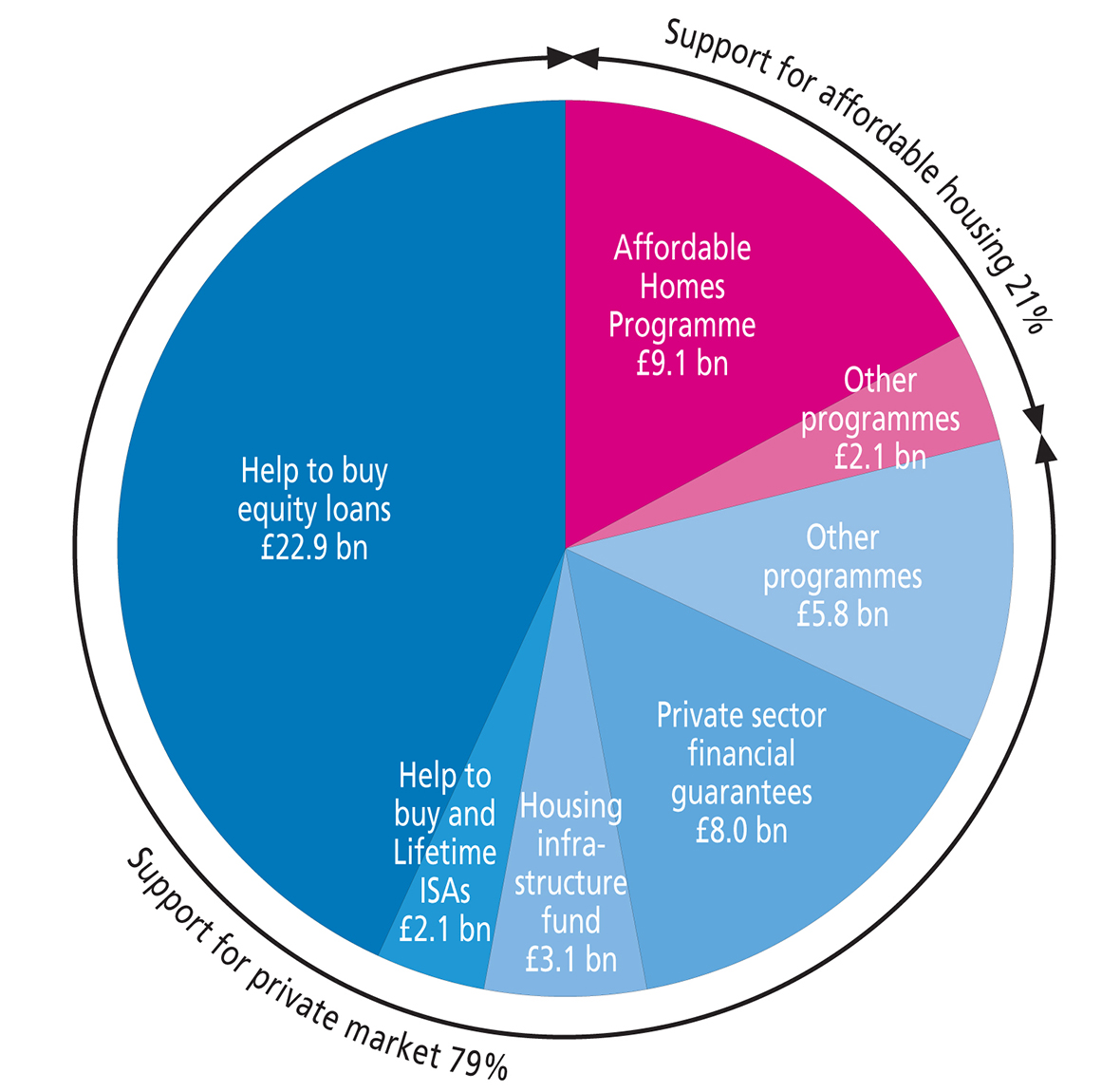

Instead, the government shifted its investment priorities away from affordable housing altogether, and towards the private market.

Our final chart shows the result. It looks at all the ways the government is incentivising housing investment in England over the period to 2020/21.

Whereas calculating this used to be straightforward, now it’s more complicated because there are so many different ways in which the government stimulates the private market – whether by direct spending, loans or guarantees. The chart lumps all of these together:

Doing this shows just how much money in different forms is going towards supporting the private market, whether it be Help to Buy equity loans, ISAs, financial guarantees or other incentives.

Add all these up and they total 79% of government investment support, leaving aside spending on housing benefit and other forms of personal subsidy.

Affordable housing investment, mostly the programmes administered by Homes England and the GLA, gets a mere 21%.

“Why has such a huge shift in spending taken place with practically no public discussion of how much support the private market should receive?”

Taking a long view of how government spending on housing has changed offers some lessons for priorities now. First, while it may be right to help first-time buyers, should it dominate spending priorities at the expense of investment in homes at genuinely affordable rents?

Why has such a huge shift in spending taken place with practically no public discussion of how much support the private market should receive and whether the money is well spent?

Secondly, it is notable how intent the governments of 40 years ago were on investing in bricks and mortar.

“It was not long ago that governments of both main parties saw building homes to let at modest rents as the key aim of a sensible housing policy.”

Instead of investing to keep rents down, we have been content to let them soar then start attacking the inevitable rise in housing benefits.

There is an urgent need for a vision of social housing which shows how investment now will enable us to reduce the numbers who need benefits to pay their rents, and ultimately to bring down the benefits bill.

Looking back on the significant investment that took place in the late-1970s, or even at the recent peak in 2009/10, shows us that it was not long ago that governments of both main parties saw building homes to let at modest rents as the key aim of a sensible housing policy.

It’s time to get back to basics.

John Perry, senior policy adviser, Chartered Institute of Housing

What is the UK Housing Review?

The front cover of this year's edition

The UK Housing Review is published and sold every year by the Chartered Institute of Housing.

This year's edition is 248 pages long and features commentary, data and insight on the current state of the housing sector.

It includes information across a wide range of areas including the wider housing market, affordability of rents, economic environment, homelessness, housing need, lettings, stock condition and tenure trends.

The 2018 review was written by Mark Stephens, director of the Urban Institute at Heriot-Watt University, John Perry, policy adviser at the CIH, Steve Wilcox, former professor of housing policy at the University of York’s Centre for Housing Policy, Peter Williams, land economy departmental fellow at the University of Cambridge, and Gillian Young, honorary research fellow at Heriot-Watt University.