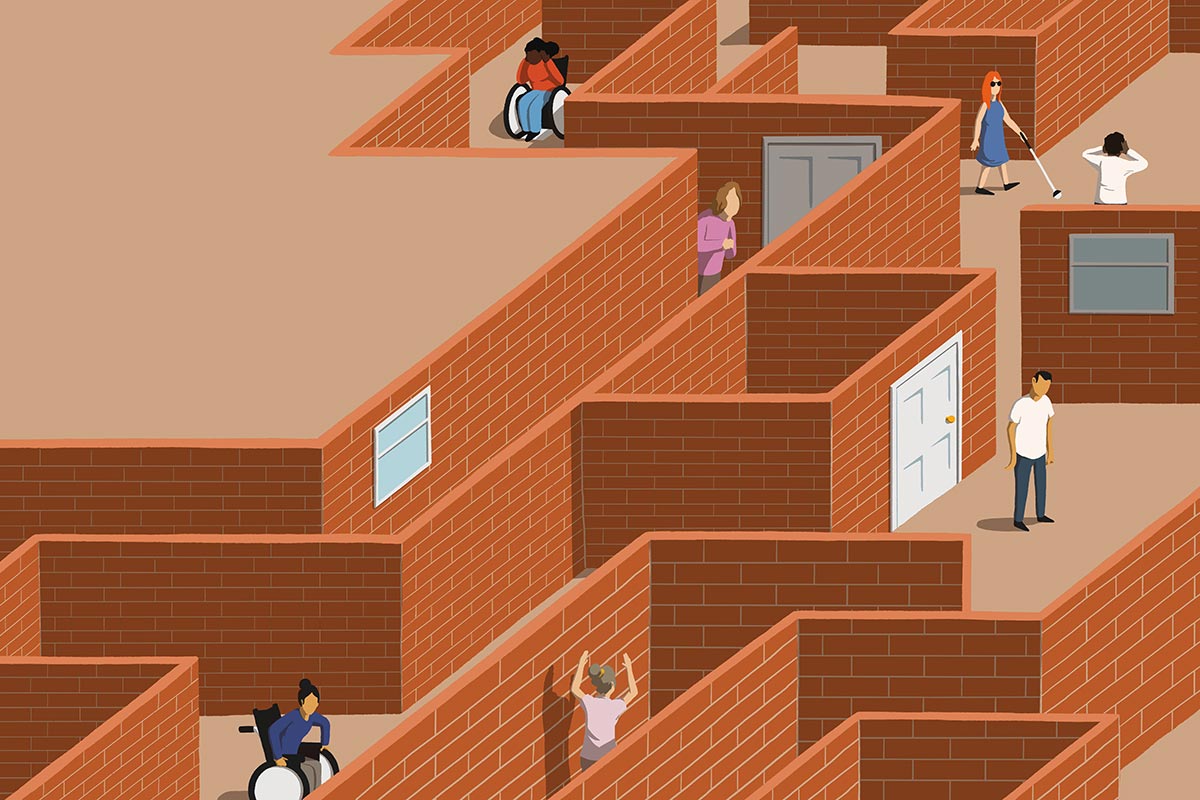

Disabled people are more at risk of homelessness – how can the sector respond?

New research has shown that disabled people are more likely to become homeless, and find it harder to exit homelessness into housing, says Lígia Teixeira

We should all be concerned about the rise in homelessness seen since the cost of living crisis began to bite in the middle of last year.

But evidence shows clearly that the risk of homelessness is skewed towards certain groups of people, because of their circumstances.

Disabled people are one such group. The latest policy paper we’ve published at the Centre for Homelessness Impact shows that disabled people are significantly over-represented among populations experiencing homelessness.

The rate of poverty, which heightens the risk of homelessness, is 27% among disabled people, and 32% if benefits specifically for costs associated with their disability are included, compared to 20% among people without a disability.

Again, we should not think in terms of one homogenous group. Disabled people face very different challenges, from people with a mental illness, and indeed from people with a neurodevelopmental condition.

Housing with lifts, ramps, mobility aids and lowered surfaces are essential to daily living for a wheelchair or scooter user. A single self-enclosed property may be the only viable option for an autistic person for whom social interaction and processing sensory stimuli are real challenges and for whom sharing living quarters in a noisy hostel, for instance, may be frightening and overwhelming.

“Disabled people are at greater risk of entering homelessness, and they face greater barriers to accessing stable, settled housing: self-exiting homelessness is more often simply not possible”

The number of households accepted as homeless by reason of physical ill health or disability rose by 73% in England between 2018 and 2022, while one survey of people experiencing homelessness found that 82% of respondents had a mental health diagnosis.

Among households assessed as homeless, 28% in England and 21% in Scotland were identified as having two or more additional support needs last year.

Our report shows that just as disabled people are at greater risk of entering homelessness, they face greater barriers to accessing stable, settled housing: self-exiting homelessness is more often simply not possible.

These obstacles include difficulties in obtaining a diagnosis from a GP, particularly where post-COVID-19 practices, such as online screening and consultations persist; meeting the threshold for a disability; a shortage of accessible housing; and the fact that unsuitable support or living conditions may worsen their health or aggravate psychosocial symptoms.

In England, only 7% of homes incorporate minimal accessibility features, and in Scotland only 0.7% of local authority housing and 1.5% of properties managed by social landlords are wheelchair accessible.

Solutions recommended by the lead author, Dr Beth Stone, a lecturer in disability studies at the University of Bristol, include more consistent responses to disabled people who are affected by homelessness, more accessible housing with bespoke support, more collaborative work by providers of services and better communication to address low uptake of services that do exist.

“I sat in dismay, listening to speaker after speaker describing the profile of homelessness in their country or region”

One thing that has struck me is the familiar pattern we see whenever we apply a lens of inequality to the issue of homelessness. The research we published on disability followed similar studies on how homelessness affects people from an ethnic minority, who are LGBTQ+ and who spend time in local authority care during their childhood.

In every instance the authors found over-representation of homelessness, poor data collection, a need for more flexible people-focused services and a weak research base, especially in evaluating targeted interventions to address homelessness. It is a disappointing picture.

I should stress, however, that this is not a problem unique to the United Kingdom. In March, I attended the Institute of Global Homelessness conference in Chicago, which brings together practitioners and academics from across the globe. I sat in dismay, listening to speaker after speaker describing the profile of homelessness in their country or region.

Contexts varied. However, root causes were the same. Disabled people were consistently among groups at higher risk of homelessness.

In fact, over those days in Chicago, I was reminded of the safety net we have in the UK that prevents rates and patterns of homelessness from being far worse: free healthcare, housing rights, social security benefits.

Homelessness in the UK is too high and must come down. And yet, we should be mindful that our rates of homelessness are lower than in most developed countries and do all in our collective power to ensure we do even better. To go from good to great we need to do even better when it comes to addressing inequalities, and the realities of people living with disabilities.

Sign up for our care and support newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters